Understanding Equity for People with Disabilities

Learn about the background of DRM’s health equity report by clicking into each subject below.

Impact of the Disability Civil Rights Movements

Disability-related disparities in healthcare are nothing new. The Disability Civil Rights Movements that gained momentum in the early 1970s paved the way for the passage of landmark civil rights legislation for those with disabilities. For the first time in U.S. history, the signing of regulations contained in Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act gave the disability community broader access to public services, including healthcare, by making it illegal for any program or entity that receives federal funding to discriminate or deny access because of disability. These rights and protections expanded further with the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990 and the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010.

Though these rights for individuals with disabilities are critical, significant obstacles remain to ensure equitable access to healthcare for the disability community. These include: a lack of attention to this unique demographic in social determinants of health strategies; diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts and curricula; healthcare data collection practices; the lack of an adequate community-based direct support workforce; and continued reliance on forced institutional living status.

To address these inequities, there must also be a shift in how we think of disability. Disability activists around the world have moved away from the medical model of disability, which seeks to fix or get rid of a condition that is medically diagnosed as a disability. This model does not adequately address the limiting factors that impact individuals with disabilities’ functioning in a society that was not designed with them in mind. Instead, disability activists embrace the social model of disability, which seeks to change the physical and social environment to be more inclusive and welcoming of all people, including those with disabilities.

Download Health Equity Report PDFUnderstanding Social Determinants of Health (SDOH)

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are non-medical factors that influence health outcomes. Housing stability, food security, access to transportation, and racial discrimination in healthcare delivery are common SDOH focus areas. Across the board, the lack of disability data and the impact of disability on SDOH lead to strategies that are insufficient to address the unmet needs of this demographic and other intersectional identity groups that are most vulnerable to healthcare inequities.

- Housing Stability and Disability

- Food Security and Disability

- Access to Transportation and Disability

- Racial Discrimination and Disability

The Importance of Disability Data

Advancing health equity is impossible without data. Data informs strategies to address inequities in healthcare delivery and the socioeconomic conditions that influence health outcomes. However, disability data is rarely collected unless it is for research solely focused on disability itself.

As described by Swenor (2022), the COVID-19 public health response is the perfect example of how the lack of disability data results in data gaps that erase inequities and social justice for the disability community. For example, in April 2020, the U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey was launched to assess the impact of the pandemic on US households. Data was disseminated biweekly to inform federal and state response and recovery planning. However, it did not include standard questions about disability until April 2021, during the second year of the pandemic (Swenor, 2022; U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). Within the first weeks that disability questions were asked in the survey (April 14 to April 26, 2021), data emerged that showed people with disabilities were at a disproportionate risk of food insecurity and experienced a lack of access to healthcare during COVID-19 (Assi et al., 2022).

Despite requirements of Section 4302 of the Affordable Care Act to include the capability for electronic health records (EHRs) to contain disability status, significant gaps in disability data in EHRs also prevented tracking of COVID-19 testing, vaccination, and mortality among people with disabilities during the pandemic (Swenor, 2022; Kaundinya, 2022). Much of the data that was available have come from people with disabilities living in congregate care settings, like nursing homes, or are limited to people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (Swenor, 2022). One of the most regularly cited statistics regarding COVID-19 and disability comes from a study by Jefferson Health which found that people with intellectual disabilities are six times more likely to die of COVID-19 infection (Gleason et al., 2021). However, one of the commonly misunderstood aspects of disability is that disability does not, inherently, affect a person’s life expectancy. Disability data gaps remove opportunities for evidence-based policies and the reach of mitigating efforts to prevent unnecessary illness and death for people with disabilities (Swenor, 2022).

Swenor (2022) further explained why disability data is critical in all spheres of study, even those outside of disability-specific issues. Limiting disability data collection to disability-specific issues creates barriers to using data sets across varying systems, including healthcare, food access, housing, transportation, education, employment, voting, etc. Therefore, disability data must become a core dimension of all demographic data. Broad disability data collection is the key to finding the root causes of health inequity for people with disabilities and other intersecting identities and developing strategies to end it.

Download Health Equity Report PDFThe Crisis of Direct Care Workforce Capacity

Workforce capacity is critical in health equity and the healthcare system’s response to public health emergencies. While hospital workforce shortages were a focal point of the COVID-19 public health emergency, long-standing direct-care workforce shortages also reached crisis levels during the pandemic.

The Administration for Community Living reported that millions of people who depend on home and community-based services to maintain their independence experienced service disruptions or were forced to move into nursing homes or other institutions, compromising their health and safety during the pandemic (2022).

This crisis did not end with the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency. Recent reports show that more than three-quarters of direct care service providers are not accepting new clients, and more than half have cut services because of the direct care workforce shortage. In addition, high direct care staff turnover averages nearly 44 percent across states (National Core Indicators Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities [NCI IDD], 2022).

The direct care workforce crisis is not only a public health concern for individuals with disabilities. The Administration for Community Living laid out key issues fueling the crisis, including poor wages and lack of benefits, including health insurance, for direct care workers themselves (2022). Therefore, health equity strategies must include initiatives to improve the recruitment and retention of direct care workers. The health of millions of people with disabilities and those who provide their direct support services depend on it.

Institutional Bias

Other than hospitals, the devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic was most pronounced in nursing homes and long-term care facilities that house older adults and people with disabilities that are prone to the harshest consequences of COVID-19 infection (New York Times, 2020). As concluded in a cohort study by Bartley et al. (2018), even in non-emergency times, there are significant health benefits to community-dwelling versus living in congregate care settings. Unfortunately, though most prefer to live in their own homes, it can be difficult for people who have long-term care needs to maintain an adequate level of support to do so. Historical institutional biases in the Medicaid program and in patterns of healthcare spending in Michigan contribute to the lack of community housing choices for members of the disability community.

Download Health Equity Report PDFDRM Vaccination Program

From 2021 to 2023, DRM formed the Vaccine Advocacy Team (VAT) for COVID-19 work. In order to provide the best care, DRM contracted with one of the providers, DocGo, directly to broaden vaccination and community engagement efforts. This included community centers, homeless shelters, public housing settings, and permanent supported housing. DRM also worked with a parallel rollout of mobile vaccine services provided by the Wayne Health Mobile Unit, working with Wayne State University’s Developmental Disabilities Institute to collaborate on vaccine events such as the Special Olympics in Detroit.

The Impact

4,208 individuals received COVID-19 vaccinations from the beginning of the project through June 2023.

-

2,846 vaccinations administered directly by DRM’s contract clinical provider (68%)

-

738 vaccinations indirectly facilitated by DRM staff at events with other providers (17%)

-

624 vaccinations referred to mobile clinics (15%)

Communication Efforts

VAT staff crafted messaging that was specifically designed to reach everyone, even those who typically experience communication barriers or have limited access to the internet. Special care was taken to ensure all communications met disability accessibility standards. Due to DRM messaging, over 63,000 people received information about vaccines, DRM, and its vaccination activities by the end of June 2023.

Community Engagement

Since the early stages of DRM VAT project work, VAT staff has established numerous partnership agreements with outside groups to share DRM Vaccine Advocacy information and/or host community vaccination clinics. Community engagement and partnerships are the bedrock of DRM’s vaccine advocacy success. Even organizations and groups without a specific focus on disability had valuable insight into the needs of their communities. These needs inherently intersect with those of people with disabilities. DRM VAT staff took a backseat in planning vaccine outreach as much as possible, allowing community leaders to lead, while DRM facilitated mobile health services and offered support.

Advocates can learn important lessons from DRM vaccine work. Widening the net of engagement to community leaders and marginalized groups beyond the disability community, while keeping a focus on accessibility and inclusion for those who have disabilities, maximizes impact. Health equity strategies that target only those who have medically defined disabilities may miss many with complex, intersectional identities and needs. To improve access to healthcare and healthy living opportunities, disability must be integrated, not singled out.

Health Equity Clinic Stories

Read about the stories of individuals attending DRM vaccination events who spoke volumes about the lack of health equity in the communities served. Here are some examples taken from one event at a south-central Michigan homeless shelter:

Home-Based Vaccination Stories

DRM also facilitated over 350 home-based vaccinations through June 2023. Most of these individuals were referred to DRM by their local health departments, Area Agencies on Aging, home care providers, hospice agencies, or Disability Networks. Some of the recipients included:

First Project Survey

In June 2022, DRM released a survey report based on 155 completed vaccine survey responses with recommendations and implications for future healthcare. Recommendations were based on the following survey-identified barriers to vaccination:

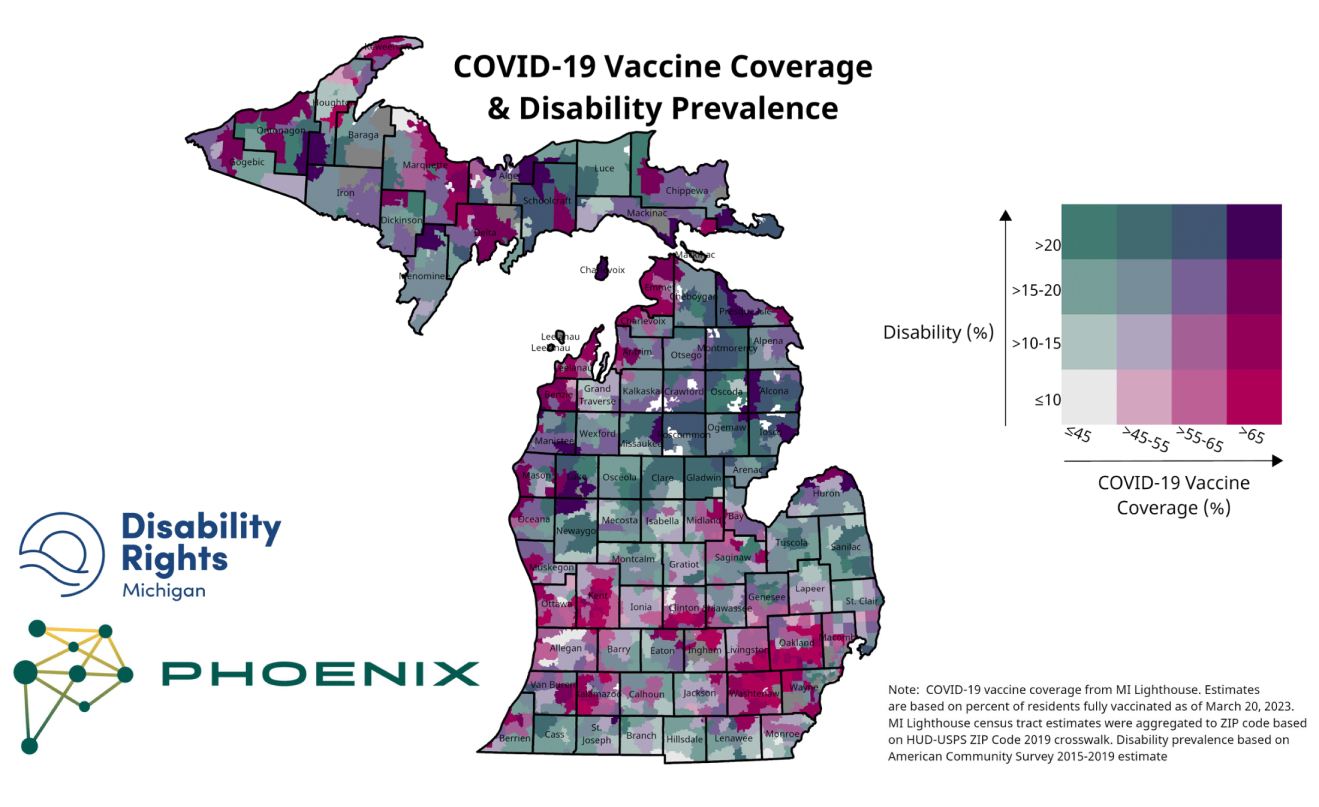

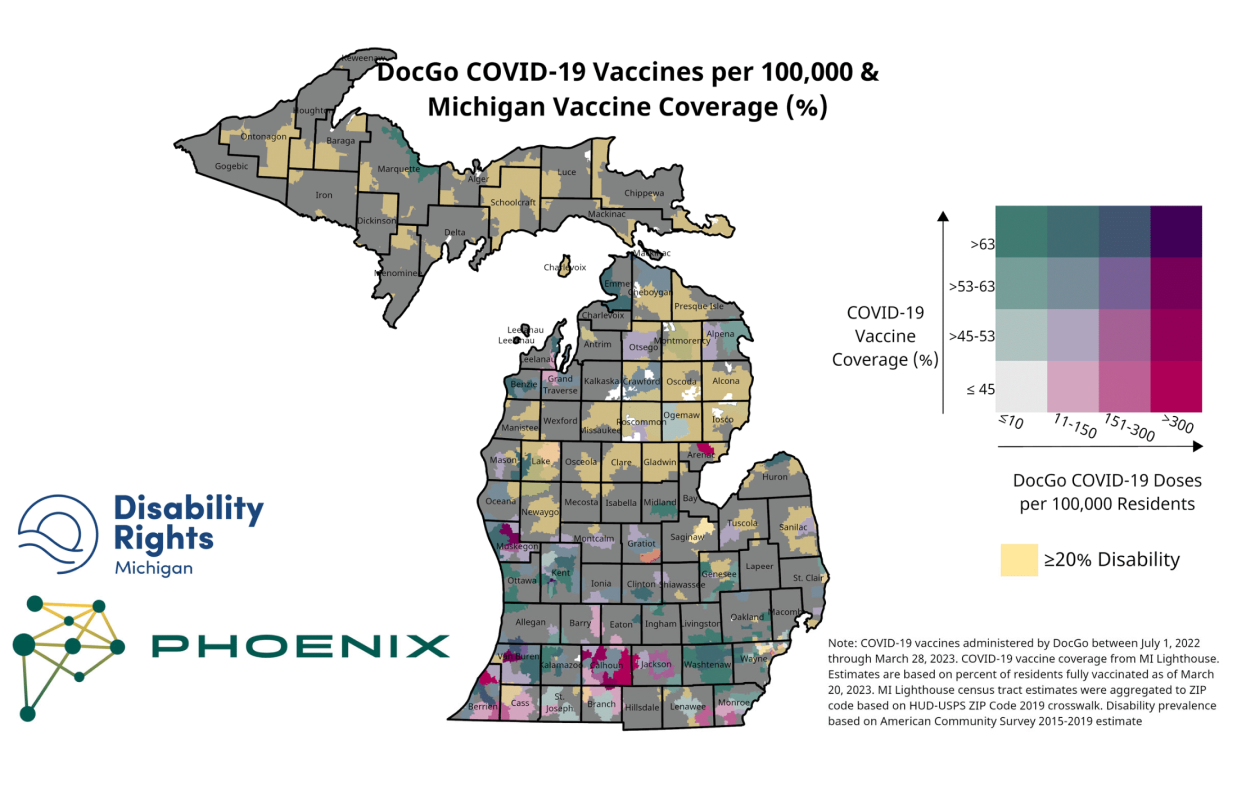

Data Mapping

DRM VAT staff facilitated the creation of heat maps overlaying community and homebound COVID-19 and flu shots facilitated by the DRM VAT team with vaccination uptake and disability prevalence. VAT staff used these maps to measure progress in targeted regions of the state and evaluate future vaccine outreach targets. Staff also shared the heat maps with grant and community partners to measure collective impact and evaluate future collaborative work.

Focus Groups

In August 2023, DRM VAT staff facilitated two focus group sessions to gauge the impact of disability within the context of the health equity landscape. Eligibility to participate was based on the following factors:

- Must reside in Michigan

- Must fit into at least one of the following categories:

- Have a disability.

- Be a relative of or have a close personal relationship with a person or people with disabilities.

- Work directly for or have a professional relationship with a person or people with disabilities.

Recommendations

The findings of this report emphasize the need for significant systemic changes to advance health equity for Michigan’s disability community. The following recommendations address health equity gaps and successful interventions of the DRM Vaccination Project.

Conclusion

The COVID pandemic left an indelible mark on the disability community and their allies. "The Coronavirus pandemic has disproportionately impacted people with disabilities, not because the virus targets disability, but because long-standing shortcomings in numerous systems predictably left us vulnerable," said National Council on Disability Chairman Andrés Gallegos in October 2021 (National Council on Disability). At the same time, the response to the pandemic brought with it lessons on what happens when our support systems eliminate barriers to care and support and provide sufficient resources to combat health issues. It is our hope that these valuable insights will not be lost, both as tools for responding to future crises and as guidance for addressing longstanding institutional and cultural issues affecting people with disabilities.

Learn More About Health Equity

Download the full DRM Health Equity Report to dive deeper into the wealth of detailed information and access all the valuable sources found in our comprehensive report.

Report Sources and Endnotes

- National Council on Disability (2021, October 29). Progress report: The impact of COVID-19 on people with disabilities. https://ncd.gov/sites/default/files/NCD_COVID-19_Progress_Report_508.pdf

- Lurie, K., Schuster, B., & Rankin, S. (2015). Discrimination at the margins: The intersectionality of homelessness & other marginalized groups. Homeless Rights Advocacy Project, 8. https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/hrap/8

- Cassidy, J. (2022, March 17). Homes for a lifetime: Housing justice for older adults and people with disabilities. Michigan League for Public Policy. https://mlpp.org/homes-for-a-lifetime-housing-justice-for-older-adults-and-people-with-disabilities/

- Butrica, B., Mudrazija, S., & Schwabish, J. (2022, March 31). The geography of disability and food insecurity. The Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/The%20Geography%20of%20Disability%20and%20Food%20Insecurity.pdf

- Ives-Rublee, M., & Sloane, C. (2021, December 21). Alleviating food insecurity in the disabled community: Lessons learned from community solutions during the pandemic. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/alleviating-food-insecurity-in-the-disabled-community/

- Henning-Smith, C., Worrall, C., Klubunde, M., & Fan, Y. (2020, July 1). The role of transportation in addressing social isolation in older adults. The National Center for Mobility Management. https://nationalcenterformobilitymanagement.org/resources/the-role-of-transportation-in-addressing-social-isolation-in-older-adults/

- Simard, J., & Volicer, L. (2020). Loneliness and isolation in long-term care and the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(7), 966–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.006

- Eldercare Locator (2021). 2021 Eldercare Locator data report infographic. https://eldercare.acl.gov/Public/About/docs/EL_Data_Report_infographic_2021_508.pdf

- Eldercare Locator (2018). 2018 Eldercare Locator data report. https://eldercare.acl.gov/Public/About/docs/EL-Data-Report.pdf

- Ryerson, A. B., Rice, C. E., Hung, M.-C., Patel, S. A., Weeks, J. D., Kriss, J. L., Peacock, G., Lu, P.-J., Asif, A. F., Jackson, H. L., & Singleton, J. A. (2021). Disparities in COVID-19 vaccination status, intent, and perceived access for noninstitutionalized adults, by disability status — National immunization survey adult COVID module, United States, May 30–June 26, 2021. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70(39), 1365–1371. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7039a2

- Myers, A., Ipsen, C., & Lissau, A. (2021). America at a glance: COVID-19 vaccination among people with disabilities. University of Montana, Rural Institute Research and Training Center on Disability in Rural Communities. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1053&context=ruralinst_health_wellness

- University of New Hampshire Institute on Disability. (2023). 2023 Annual disability statistics compendium supplement: Part of the 2023 Annual Disability Statistics Collection. https://disabilitycompendium.org/sites/default/files/user-uploads/2023_Annual_Disability_Statistics_Supplement_ALL.pdf

- Rahman, N. (2022, September 16). Michiganders with disabilities are living in poverty, struggling to afford basics. Detroit Free Press. https://www.freep.com/story/news/local/michigan/2022/09/16/michiganders-with-disabilities-are-struggling-to-make-ends-meet/10229475002/

- Transportation Riders United. (2020, June 1). Advocate: Regional transit funding. https://www.detroittransit.org/support-regional-transit-investment/

- Milefchik, K. (2018). Disability and transportation in Southeast Michigan. Transportation Riders United. https://www.detroittransit.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Disability-and-Transportation-in-Southeast-Michigan-Report-2.51.pdf.

- Kostyniuk, L. P., St. Louis, R. M., Zanier, N., Eby, D. W., & Molnar, L. J. (2012). Transportation, Mobility, and Older Adults in Rural Michigan. University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute. Retrieved from https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/91979/102872.pdf.

- O'Connell-Domenech, A. (2022, July 22). The Hill, Changing America. Uber Doesn't Have to Offer Wheelchair-Accessible Rides in Every Market, Judge Rules. Retrieved from https://thehill.com/changing-america/respect/equality/3578440-uber-doesnt-have-to-offer-wheelchair-accessible-rides-in-every-market-judge-rules/.

- Condon, S., Darvin, A., Jones, P., Kemp, C., Lizundia, C., Rivers, S., Weisman, S., & Yu, A. (2022). Evaluating funding for public transit to advance Michigan's climate goals. University of Michigan Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/taubmancollege/docs/evaluating_funding_for_public_transit_to_advance_m.

- Rhyan, C., Turner, A., Beaudin-Seiler, B., Obbin, S., Lupher, E., Schneider, R., & Dennis, E. P. (2023, July). Michigan's path to a prosperous future: Health challenges and opportunities. Paper 3 in a five-part series. Altarum, Citizens Research Council of Michigan. Retrieved from https://www.bridgemi.com/sites/default/files/2023-08/MI%20Pop%20Study%20Health%20report%20%281%29.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, August 16). Racism and health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/racism-disparities/index.html

- Ndugga, N., Hill, L., & Artiga, S. (2022, November 17). Covid-19 cases and deaths, vaccinations, and treatments by race/ethnicity as of fall 2022. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/covid-19-cases-and-deaths-vaccinations-and-treatments-by-race-ethnicity-as-of-fall-2022/

- Gleason, J., Ross, W., Fossi, A., Blonsky, H., Tobias, J., & Stephens, M. (2021, March 5). The devastating impact of COVID-19 on individuals with intellectual disabilities in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.21.0051

- Aliseda-Alonso, A., Lis, S. B., Lee, A., Pond, E. N., Blauer, B., Rutkow, L., & Nuzzo, J. B. (2022). The missing COVID-19 demographic data: A statewide analysis of COVID-19–related demographic data from local government sources and a comparison with federal public surveillance data. American Journal of Public Health, 112(8), 1161–1169. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2022.306892

- The United States Government. (2021, June 25). Executive order on diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility in the federal workforce. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/06/25/executive-order-on-diversity-equity-inclusion-and-accessibility-in-the-federal-workforce/

- National Council on Disability. (2019, November 6). Quality-adjusted life years and the devaluation of life with disability: Part of the bioethics and disability series. National Council on Disability. https://ncd.gov/sites/default/files/NCD_Quality_Adjusted_Life_Report_508.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, May 15). Disability impacts all of us infographic. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disability-impacts-all.html#:~:text=Up%20to%201%20in%204,and%20people%20with%20no%20disability.

- Swenor, B. K. (2022, August 22). A need For disability data justice. Health Affairs Forefront. https://doi.org/10.1377/forefront.20220818.426231

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). Household Pulse Survey. Census.gov. https://www.census.gov/data/experimental-data-products/household-pulse-survey.html

- Assi, L., Deal, J. A., Samuel, L., Reed, N. S., Ehrlich, J. R., & Swenor, B. K. (2022). Access to food and health care during the COVID-19 pandemic by disability status in the United States. Disability and Health Journal, 15(3), 101271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2022.101271

- Kaundinya, T. (2022, February 14). The need for disability documentation in the electronic health record. Health Affairs Forefront. https://doi.org/10.1377/forefront.20220209.110739

- The New York Times. (2020, June 27). Nearly one-third of U.S. coronavirus deaths are linked to nursing homes. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-nursing-homes.html#:~:text=Deaths%20in%20long%2Dterm%20care,since%20the%20vaccination%20rollout%20began.

- Bartley, M. M., Quigg, S. M., Chandra, A., & Takahashi, P. Y. (2018). Health outcomes from assisted living facilities: A cohort study of a primary care practice. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 19(3), B26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.12.079

- National Core Indicators Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. (2020). 2020 Staff Stability Survey Report. legacy.nationalcoreindicators.org. https://legacy.nationalcoreindicators.org/upload/core-indicators/2020StaffStabilitySurveyReport_FINAL.pdf

- Administration for Community Living. (2022, October 21). ACL launches national center to strengthen the direct care workforce. acl.gov. https://acl.gov/news-and-events/announcements/acl-launches-national-center-strengthen-direct-care-workforce

- Goodman, N., Morris, M., Boston, K., & Walton, D. (2017, September 13). Financial inequality: Disability, race and poverty in America. National Disability Institute. https://www.nationaldisabilityinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/disability-race-poverty-in-america.pdf

- Pan American Health Organization, & World Health Organization. (n.d.-a). Social determinants of health. PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization. https://www.paho.org/en/topics/social-determinants-health

- Patient financial incentives for preventive care. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. (n.d.). https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/take-action-to-improve-health/what-works-for-health/strategies/patient-financial-incentives-for-preventive-care.

- Wayne State University. (2023). How to become MVP Certified. Michigan Developmental Disabilities Institute. https://ddi.wayne.edu/mvp/certified

- Leahy, A. (2022, November 16). Disability and ageing – time to think outside our silos? Centre for Ageing Better. https://ageing-better.org.uk/blogs/disability-and-ageing-time-think-outside-our-silos

- Van der Horst, M., & Vickerstaff, S. (2022). Is part of ageism actually ableism? Ageing & Society, 42(9), 1979-1990. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20001890

- Grace, V. (2019, February 6). Show up authentically: Life at the intersection of disability and multiple identities. RespectAbility. https://www.respectability.org/2018/09/show-up-and-blend-life-at-the-intersection-of-disability-and-multiple-identities%E2%80%A8/

- Iezzoni, L.I., Rao, S.R., Ressalam, J., Bolcic-Jankovic, D., Agaronnik, N.D., Lagu, T., Pendo, E., Campbell, E.G. (2022) US physicians' knowledge about the Americans with Disabilities Act and accommodation of patients with disability. Health Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01136

- Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. (2021). Accessibility at Michigan vaccination sites. State of Michigan. https://www.michigan.gov/-/media/Project/Websites/coronavirus/Folder15/Accessible_-_Accessibilty_at_Michigan_Vaccination_Sites_033021.pdf?rev=57d41906226442498ed629f0db59c9df

- Feldner, H. A., Evans, H. D., Chamblin, K., Ellis, L. M., Harniss, M. K., Lee, D., & Woiak, J. (2022). Infusing disability equity within rehabilitation education and practice: A qualitative study of lived experiences of ableism, allyship, and healthcare partnership. Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences, 3, 947592. https://doi.org/10.3389/fresc.2022.947592

How Can We Help? Contact Us Anytime.

We want to hear from you! Whether you're looking for advocacy, have a question, or just want to connect, please reach out.